At the tender age of 17 I was offered a scholarship to New College, Oxford. But you may find it hard to believe how that happened…

So let’s start with a little background. Because it’s not possible to tell this story without talking about my parents.

My father – Len Scott…

Picture a self-educated, self-opinionated and painfully self-aware man from a working-class background, who grew up in a household where financial security was far from assured. With a piercingly sharp intelligence and a well-developed skill as a writer. A man who felt lucky to land a job with a newspaper in the Depression – and stuck with it for the rest of his life, even though he hated it. Who could and should have gone to university, but never got the chance. A man who wasn’t even sure he wanted children – but found himself responsible for a tiny, sickly child born in London during the Great Smog of 1952. (Which killed literally tens of thousands, mostly the very young and the very old.)

And who then sank every penny he had into a house in the country to get that child away from the polluted air of the capital.

Which was just the beginning. Because my father nurtured, encouraged, and loved a son who had arrived late in his life. And, in his own words, took complete responsibility for bringing that son into the world.

When I expressed an interest in exploring English literature in more depth, that remarkable man came up with a reading list that started with ‘Beowulf’. I got so fascinated with the early stuff that I barely made it as far as Shakespeare.

So when I took my opportunity to take the Oxford Entrance Exam – before taking my A levels – I jumped at it. And my focus on early English literature was written into almost every page of my answers.

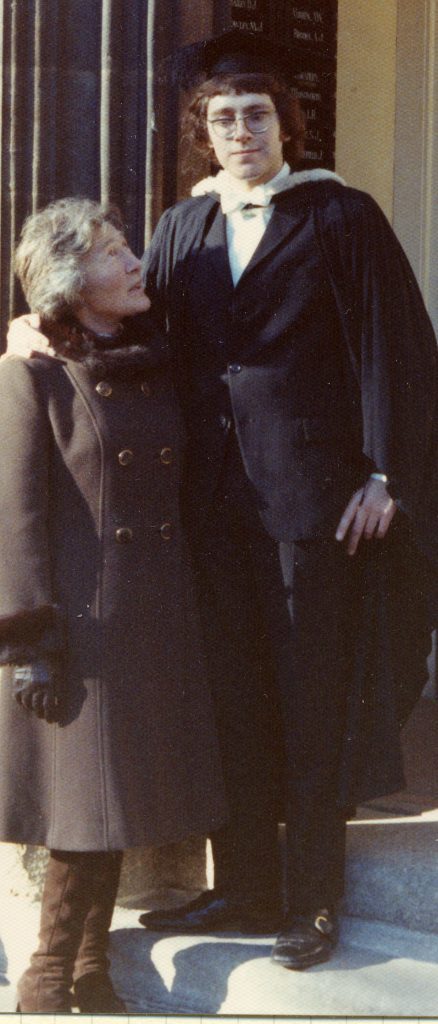

My mother – Minna Scott…

Picture a woman who had her first and only child – with considerable difficulty – at the age of 42. After a life so full of changes, triumphs and setbacks that it would make a three-decker novel.

Picture a woman who had her first and only child – with considerable difficulty – at the age of 42. After a life so full of changes, triumphs and setbacks that it would make a three-decker novel.

Minna was born to a well-off family in Copenhagen. One of seven children of a dealer in fine porcelain – who lost most of his money when the family bank collapsed. Fiercely dedicated to her own education after being forced to leave her expensive school at 15. Fluent in English and German – and with a good knowledge of French. Able to do complex calculations in her head, as she set prices for her father’s wares based on that day’s exchange rates. Married when she met my father, halfway up a Dolomite. (Yes, really!) Yet willing to divorce her wealthy husband and leave her country to be with Len.

Minna was a volunteer for the ATS before the outbreak of a war they both foresaw. Easy enough after they’d encountered Blackshirts singing ‘We march on England!’ during a walking holiday in Germany. Effectively rejected by the Army after the invasion of Denmark – an experience that led to her mental collapse. Converted to the Catholic faith while my father was serving in the Pay Corps in Algiers and in Italy – a decision that nearly broke their marriage. And then left to raise a vulnerable child in a country village where she was regarded with suspicion and, sometimes, contempt.

She did a great job. And part of that job was ensuring that I met all my Danish family, and – by doing so – learned to speak Danish as a very young child. Pretty well fluently…

Which meant that my answers to questions about language benefited not just from the French, German and Latin I had learned at school, but from my intimate familiarity with a fourth language.

My interview

When I arrived at New College it was, frankly, love at first sight. Everything about the place appealed to the romantic fantasy writer I had become, and would continue to be long afterwards. But I still remember the apprehension I felt as I walked up the stairs to the study where my interview would take place. And knocked on the door.

Apprehension which faded imperceptibly into amusement when the door opened. And a small, round, rather balding head wearing small, round glasses appeared, smiling in welcome. I couldn’t help thinking of hobbits.

‘Mister S.. S…Scott?’

‘Yes…’

‘C… c… c… come in.’

My welcomer was none other than John Bayley, husband of Iris Murdoch, who would later write the story of her tragic decline into Alzheimer’s. But all that was in the far future. As I entered the smoky atmosphere of his study I saw a tall, lean figure lounging across an armchair. He was holding a pipe that was clearly responsible for most of the smoke.

‘This is Mr T… T… Tolkien’

‘Good afternoon,’ said Mr Tolkien. And yes, this was Christopher Tolkien, son of J R R Tolkien, author of ‘Lord of the Rings’ – a book I had already read twice, and which had prompted my own dramatically overwritten forays into creating fantasy fiction.

But it would be John Bayley who began the interview. Which – to begin with – involved navigating a perilous path between stacks of paper on the floor to the chair he was offering me.

To my delight he had picked up from my exam papers both my keen interest in Old and Middle English and my love of the Danish language. It was a subject that clearly fascinated him, too. ‘They do make so much use of the glottal stop, don’t they?’ he said. I grinned. ‘Yes, as in “rødgrød med fløde”. That’s the phrase they use to torment foreigners who want to learn Danish…’

Mr Tolkien proved a harder taskmaster, grilling me thoroughly on my barely acquired knowledge of the history of the language. But while he was forensic, he was not unkind – and at the end of the interview I was more than a little surprised when Bayley said ‘Well – we’re very impressed, Mr Scott!’

Effectively, they were telling me that I had won a place. But that wasn’t quite the end of the story.

Some weeks later, on a Saturday evening, we were, as usual, enjoying the company of my father on the one day when he was home for the evening. (As a journalist, he left for work at lunchtime and returned on the last train back from London).

There was a knock at the door. And an embarrassed postman stammering apologies – and clutching the telegram he had failed to deliver earlier.

He was still apologising when I pretty much snatched it from his hand.

It was from Oxford – and it said, quite simply: ‘New College offers scholarship. Congratulations.’

So I’ve often wondered. Did I get my scholarship just because I could actually say ‘rødgrød med fløde’…?

And some acknowledgements…

It would be unfair if I failed to acknowledge my huge debt to the teachers at Caterham School who believed in me, supported and encouraged me, gave me extra tuition, and even helped me find the college best suited to my intended studies. Between them they helped me ‘shoot for the moon’ – and get there, too. Geoffrey Chant encouraged my reading of Chaucer and Gower, John Roughley gave me a crash course in Old English, and Philip Burns graciously accepted that I’d chosen English rather than History – though my choice effectively combined the two.

My Headmaster was less enthusiastic. He saw only the boy who was so uninterested in sport that he was caught playing recorder consorts while waiting to be bowled out at cricket. (Which happened pretty much as soon as the bowler got a line on the wicket). Who detested athletics and gymnastics. And who loathed rugby with a passion. ‘That boy,’ he had apparently said, ‘will never get into Oxford.’

Further comment is probably superfluous…

A well–written account of your life-changing achievement, Allan! I hope I may copy and paste into my ‘documents’ file. Perhaps at some point to print out and put with the CD of you, myself, and Mike talking about Oxford. Astonishing far-off days.

You’re more than welcome to do so, Deb. I may need to add a footnote…!

…and I now have added said footnote…

I am left wondering did you take your A levels, or just go up to Oxford?

I did take them (the university wanted two Es and I got two As and a C plus an A in my English S-level – the only one my headmaster let me take, though I had prepared for a History S-level as well). The As were for English and History, the C for Latin, which I took because so many other languages descend from it.